Why I chose OpenAI over academia: reflections on the CS academic and industry job markets (part 2)

February 12, 2023At the end of my job search, I did something I totally wasn't expecting. I turned down all my academic job offers and signed the OpenAI offer instead.

I was nervous and stressed out during my decision-making process -- it felt like a U-turn at the time -- but in the end I'm really happy with how things turned out. There were two key factors at play for me:

1) I felt like I could best pursue the work I'm passionate about at OpenAI, and

2) San Francisco -- where OpenAI is -- is an amazing city for my partner and I to live and work.

I'll discuss my decision-making process more in this post.

Why I'm writing this post

When I was job hunting, I got a lot of great advice from professors in my network about how to apply for jobs, how to interview, and how to create a strong application. I tried to distill this advice on a post about experience applying for jobs, in the part 1 of this series.

However, when it came time to decide, I felt a bit more alone. Granted: I feel super lucky for having such a strong network of professors and industry researchers, who I feel like I can contact about these things. But deciding between career paths is more of a bespoke personal decision, where to some extent there's "no right answer."

Another factor that influenced my decision: most people I knew seemed to have already chosen a side between academia and industry. Most of the professors I knew were firmly in the academic system (though also dabbling in industry on the side), while most of the people I knew in industry had never seriously considered academia as a career.

(This felt extra weird for me because, mid-PhD, I decided to go on the 'academic track' because doing so would allow me to put off such a final decision between academia or industry: the common wisdom is that it's easier to switch from academia to industry versus the other way around. Fast forward a few years though, and it felt like being on academic track was a part of my professional identity, many of my peers were doing the same thing, and so it felt like momentum was pushing me towards the academic route.)

Anyways, I'm writing this post to offer an n=1, opinionated, perspective on how I came to my own decision between some pretty different options. (And perhaps to help answer people who email me asking for advice in their case!).

A few disclaimers: the opinions in this post are just my own. I'm not trying to give general advice: I don't feel qualified to give it (I've never tried my hand at being a professor after all). Moreover, a significant factor behind my decision was that it feels like my field is in a pretty unique situation right now (more later!), which isn't necessarily true for all fields.

Instead, I'm going to try to be as open as possible about my own experience. I'm also going to be writing this from my perspectives around late Spring 2022, when I was deciding. Doing so is probably more relevant for others deciding: the reason these decisions are hard is that no one has a crystal ball about what the future will hold. That said, I'm really enjoying it here at OpenAI, and I don't regret my decision at all. My thoughts on research and the field have evolved (and will continue to evolve!) learning from all the great people here; they might just have to wait for another post.

My perspective on my work -- and goals -- shifted during my academic job search

For context, I did my PhD at the University of Washington, from 2016 to 2022, and really enjoyed it. My research is on multimodal AI: I build machine learning systems that understand language, vision, and the world beyond.

As I wrote about in part 1 of this series, my research interests shaped my intended career path. I'm most excited about doing basic research and mentoring junior researchers. At least traditionally in computing, this is the focus of academia, whereas industry specializes in applied research towards turning scientific advances into successful products.

Going on the academic job search gave me an inside look at what being a professor is like, across many different institutions and subfields of CS. I spoke with over 160 professors across all my interviews.In the end, though, I felt uneasy about whether academia was ultimately right for me.

In my field, doing large-scale basic research in academia is hard -- and getting harder

I felt like the ground was shifting under me.

Academia (and more specifically, my advisors' research groups at the University of Washington) has been a fantastic environment for me over the last six years. I was pushed to carve out a research direction that excited me. I felt generously supported in terms of advising and resources: through it, I was able to lead research on building multimodal AI systems that improve with scale that in turn yielded (to me) more questions than answers.

In contrast, during that time, most big industry research labs didn't feel like a great fit for my interests. I tried applying for internships during my PhD, but was never successful at finding a place that seemed aligned with my research agenda. Most industry teams I knew of were primarily language-focused or vision-focused, and I couldn't choose a side. I spent a lot of time instead at the Allen Institute for AI, a nonprofit research lab that felt academic in comparison.

However, I feel like the situation is changing. In my area of focus, I worry that it's hard -- and becoming harder -- to do groundbreaking systems-building research in academia.

The reality is that building systems is really hard. It requires a lot of resources, and a lot of engineering. I think the incentive structures in academia aren't very suited for this kind of costly, risky systems-building research.

Building an artifact and showing it scales well might take years of graduate student time and over $100k in unsubsidized compute costs alone; these numbers seem to be increasing exponentially as the field evolves. So it's not a feasible strategy to write a lot of papers. Now this shouldn't be the goal by any means, but unfortunately I know many academics who gravitate towards paper-count as an objective measure; plus, papers are the coin of the realm in academia - you need papers to write grants, have something to talk about at conferences, and to land your students internships, etc. Finally, at the end of the day, success at an academic career is helping students build empires and carve out their own research agendas (so they can maybe be professors elsewhere and the cycle can continue), this creates an inherent tension in contrast to the collaboration required to do great research.

It feels like the broader trend is for academics to move towards applied research, instead.

As core models become more powerful and costly to build, it pushes more academics towards building on top of them -- which is a trend I see in NLP and vision, the two spaces I've been active in. This in turn influences the problems academics study, spend time thinking about, and discussing at conferences. This trend means there are fewer papers about how to build these systems being presented at conferences (of course there are other factors for this too!).

To me, this suggested that the window of opportunity, at least towards my original research vision, was closing fast in academia. Suppose I was super successful at raising money, building out an amazing lab of researchers, and nudging them towards doing amazing things -- all super difficult things that can take years of sustained hard work. After all that time, would there still be a constituency for the research I'm excited in? If the current rate of progress of the field continues -- marked by seemingly exponential progress both in capabilities as well as the price to entry -- there might be no academic researchers working in that space in 7 years, around the time when I'd need to go up for tenure. It's a wild thought, but then again, the progress over the last 7 years has been pretty wild.

More realistically, I'd need to change my research direction. That wasn't something I wanted to do, though, and it's probably the main reason I ended up going the industry route.

Other differences between academia and industry

My thoughts on research -- which are of course specific to the field I work in -- were the most important factor in my decision. I was also considering a bunch of different things though:

Single-tasking on important problems. I was worried about all the other responsibilities professors have: teaching (and preparing teaching materials), doing department and field service, setting up and managing computing infrastructure, applying for grants and managing money. Though I find a lot of those things fun and exciting, especially teaching, I don't think I'd like the constant context switching the job entails. A friend described it to me as "a million little ants eating at one's time."

In contrast, during my PhD I enjoyed focusing deeply on one important research problem at a time. I think that's a lot easier to do in industry. Doing experiments and writing code is really tough as a professor, but in industry, there are more options along the spectrum between individual contributor and manager.

Prestige and money. I think a lot of people are subconsciously attracted to academia because it feels prestigious and exclusive. I'm not into this. I think focusing on rankings and prestige chases the wrong things, and in doing so can create a stale and toxic environment. On the other hand, many people are attracted to industry because it offers higher salaries (understandably important). I'm really fortunate that I could focus mostly on finding an environment that brought me more intrinsic satisfaction, first and foremost.

Job security versus profession security. I think many people misunderstand tenure, academics and nonacademics alike. Tenure is job security; it's more difficult for professors to be fired. But the byzantine nature of the academic job market means that they have little profession security; to be able to easily change jobs. So unlike industry researchers, who even in this difficult macroeconomic climate can switch jobs easily (well, because AI is doing well relative to the rest of the industry), academics are more stuck against administrators who might assign them more responsibilities, who might cut pay, or who might make everyone teach in-person during the height of the pandemic.

(As an aside, I think the only recourse for academics is to unionize; somewhat depressingly at the University of Washington though, many CS professors had previously signed onto an anti-union statement, killing an earlier unionization drive.)

"Freedom" is complicated. In academia, I'd have freedom to work on any problem I wanted in theory, but I could be held back by not having sufficient resources, the right incentive structures, or a supportive-enough environment. I joined OpenAI because here it feels like I'm incredibly well-supported to work on precisely the problems I'm most excited about. I figured that with any industry lab, the ability to work on the problems I care about requires alignment with product, and I felt comfortable with such an arrangement here.

These were just a few of the dimensions I had to make peace with upon joining OpenAI, but I'm really glad I did. Maybe I'll write more about this later, but it's super fun here. I'm mentoring junior researchers and working in a team, I have access to ample resources, and I'm pushed to solve challenging problems that matter to me.

Life: San Francisco is a fantastic city

That was a lot written about my work. But life should be a lot more than that. In my case, I was also on the lookout for a city that would make both my partner and I happy.

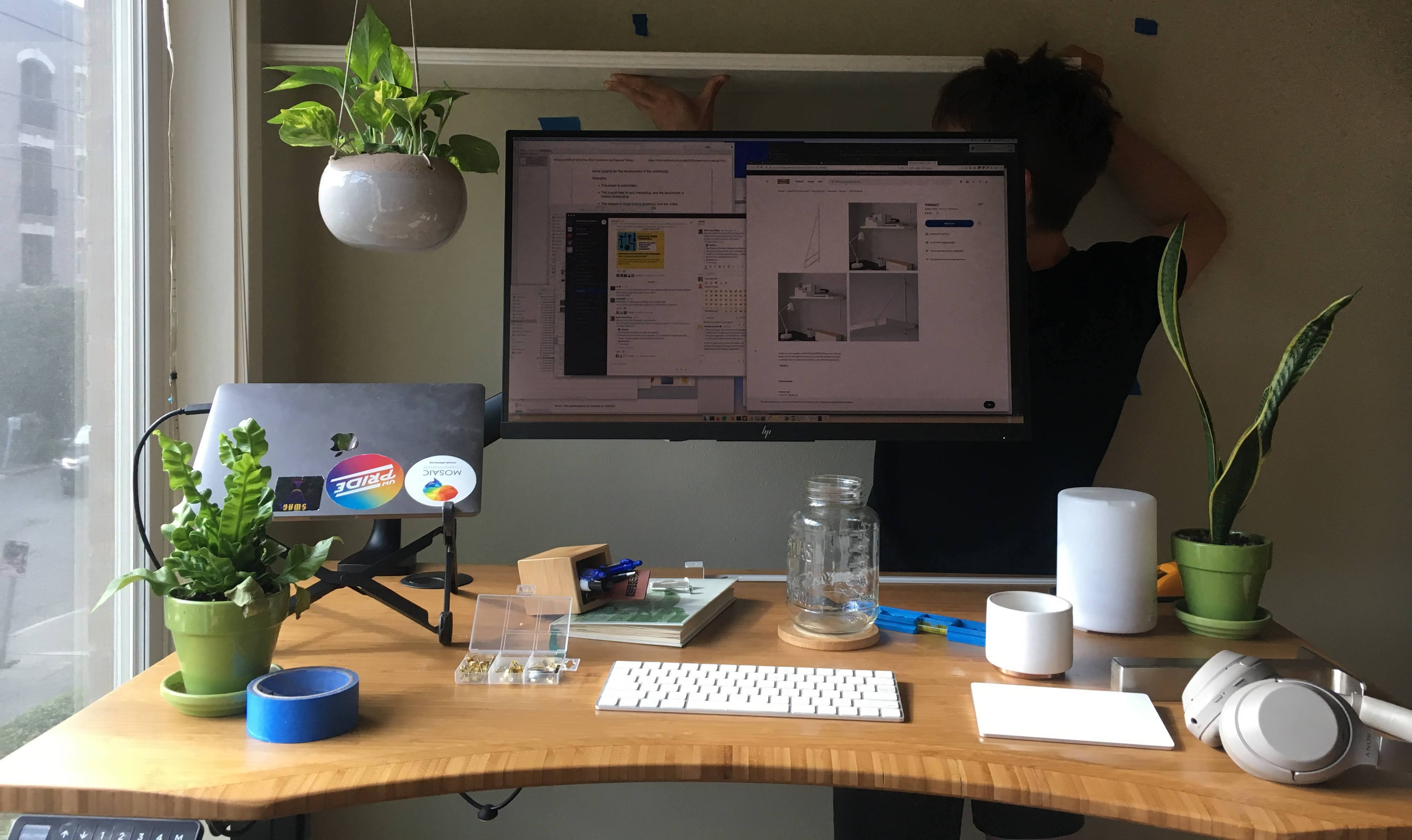

For context: my partner and I have been together for 9 years and counting. She works in technology, and her job went fully-remote during the pandemic, giving us plenty of options in theory. But we wanted a place not just that we'd tolerate, but that we'd love, ideally just as much (or as more as) Seattle, where we had spent the last 6 years. Seattle is pretty walkable by US standards, and we found it to be a great place to make friends with other young people our age, and to pursue shared interests like travel, hiking, skiing, rock climbing, and acroyoga.

On one hand, it feels privileged to write these words as someone who went on the academic job market. The academic job market is so brutal and difficult that many people have to make extreme sacrifices just to pursue what they love, especially in fields outside computing. I've heard horror stories of professors doing multi-hour commutes, or dual-academic couples accepting jobs in different cities and going long distance, just to hopefully get jobs together, some day in the future.

On the other hand, I didn't have to play that game. The indecisiveness and doubt I had about whether to go into academia or industry also gave me plenty of choices and freedom!

An impromptu vacation to Amsterdam spoiled me

I took an impromptu vacation in Amsterdam during the job search, in late April.

(Technically it wasn't really a vacation per se. I was doing a second visit at the Max Planck Institute for Informatics in Saarbrücken, and it was a direct flight from Seattle to Amsterdam; both my partner and I were invited.)

We were stoked. It feels cliché to say, but we're both young urbanist-types who love walkable cities, public transport, and bike infrastructure. And as popularized by YouTubers like Not Just Bikes; Amsterdam is the place for all these things.

Indeed, Amsterdam truly felt alive. The streets were filled with people, not cars and traffic. Riding on a bike only made it better. Once I got the hang of Dutch bicycle etiquette and what to do at intersections -- it's definitely a bit more chaotic than Not Just Bikes describes -- it felt freeing in a way that's difficult to put into words. The whole city just opens up. Just within a one-minute bike ride radius, I felt like I had so much choice about where I could find essentials like groceries, restaurants, and coffee. The only thing that slowed me down was finding bike parking.

Already, bikes were the primary means of transportation for my partner and I in Seattle. To us at least, it's a lot more pleasant than traversing the city by car (and finding parking). Yet Amsterdam was a case-study on how much truly better it could be.

Second visits to US cities

Amsterdam spoiled us when it came time to do second visits at US schools.

Now -- I feel really lucky that I got some fantastic academic job offers, and I feel grateful towards faculty at those schools for vouching for me during the chaotic hiring process.

Yet, I realized -- after not traveling at all during the pandemic, and finally getting a chance to visit Amsterdam, one of the most livable cities that blew even my high expectations out of the water -- living in a walkable city without a car makes me happy. Car-dependency is a systemic problem in the US. At some of the schools I visited, I couldn't see myself as wanting to live there for a few days, much less 7 years.

And likewise, as much as I'd probably have a bad time, my partner would have it worse. Many fantastic universities are located in college towns, where it would be a lot harder for my partner to make friends or to have a life apart from the university. If one day she wanted to go to an office again, it'd be impossible to do that -- unlike in Seattle.

San Francisco

I love the urban design of San Francisco, moreso than any US city I've gotten the chance to visit over the last few years. The city is walkable; shops, restaurants and grocery stores are at human scale; and there's a connected network of bike infrastructure and public transit.

That's not to say the city is perfect. San Francisco is expensive and there are serious issues with gentrification; I recognize that by moving here I'm helping exacerbate that problem. Though, I also appreciate that policies like rent control provide at least some protection for existing residents. In contrast, Seattle has no rent control, and so corporate landlords can easily jack up rent prices.

Regarding infrasturcture and urban design, I think it's not on Amsterdam's level (yet). Many bike lanes don't feel well-protected, and delivery drivers often park in them. I'm excited to support local organizations like the SF Bike Coalition that are making progress in tackling these issues.

One additional, but also important factor: both my partner and I grew up in the Bay Area, and have parents who live nearby. This, plus the other factors, made us realize that San Francisco would be a fantastic place to live.

Epilogue: joining OpenAI

So, that was a lengthy discussion on the factors I was weighing.

There were a few options on what I could do. It feels very common in my area to take a professor position, defer it for a year, and spend that year in industry. It's kind of like a "pre-batical" with few downsides for the researcher in question, and a lot of upsides: the ability to continue research for a year, and the ability to recruit students during the spring admissions cycle.

However, I decided against it. I was worried that I'd end up not wanting to come in the end -- and that by doing so (by signing the academic offer) I'd potentially cost the school a valuable hiring slot. I communicated this to my faculty contacts at various schools, and they were all super understanding and accomodating.

But the more I thought about it, the more it became clear what I wanted to do. I turned down all the academic offers and signed the OpenAI position full time.

Half a year out, and I'm really glad I did, for so many reasons. I'm really enjoying working at OpenAI, and both my partner and I are really enjoying living in San Francisco.

Fin. That took forever to write/edit. Let me know if it helped and if I should write more here!

Thanks to Ludwig Schmidt for feedback on an earlier version of this post.